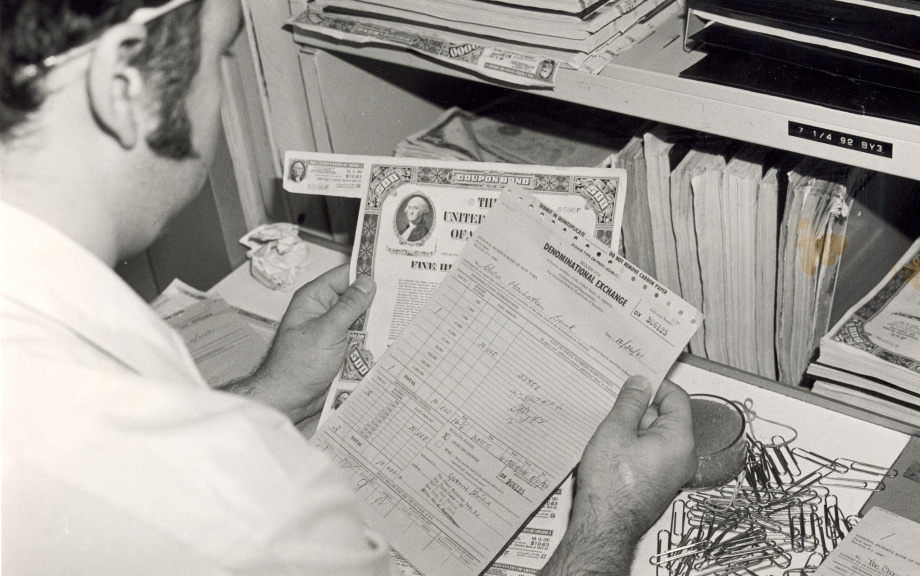

For most of modern history, stocks and bonds were pieces of paper. Sixty years ago, buying a financial security or taking it as collateral meant receiving a certificate about five days later. This worked well enough for decades, but by 1968 there was so much paper that settlement became unmanageable, and the ensuing crisis forced Wall Street to start using computers to keep track of paper securities. This transition took about four years and did not go smoothly. In the time it took for Wall Street to modernize, NASA’s Apollo program managed four moon landings.

Today, the financial industry may again be on the cusp of profound technological change. A host of central banks, banks, and other financial institutions are experimenting with “tokenizing” money and securities—that is, using distributed ledger technology (DLT) to create digital representations of these assets. For example, the New York Fed’s New York Innovation Center (NYIC) recently announced its participation in Project Agorá, an international research project exploring how tokenized money might improve wholesale cross-border payments. This article explains what tokenization is and how it works, and looks at how past innovation in financial markets might offer lessons for the future.

Tokenization’s Potential

When Wall Street modernized in the late 1960s and early 1970s, firms cooperated to “immobilize” and “dematerialize” securities, which involved locking them down physically in one place and creating electronic records. In the U.S. today, trillions of dollars of securities exist electronically inside trusted central depositories like the Fedwire Securities Service and the DTCC. With tokenization, assets can be dematerialized without being immobilized. In other words, electronic assets can move around like pieces of paper, and would not need to be held in a single, centralized ledger like they are today. This flexibility would be augmented by another aspect of DLT: “smart contracts,” or programmable rules that can automate processes. For securities, tokenization could be used to automate asset servicing, custody, and trustee tasks currently performed by intermediaries. Many argue that using new technology could materially improve settlement speed and post-trade efficiency.

Lessons from the Past

Traditionally, central banks have helped catalyze new technology in settlement—when they move, others follow. And when they do not, changes can be slow. In the 1960s, it took a crisis to force adoption of computers. Circumstances are different today—gaining a competitive trading advantage from better or faster technology is a ubiquitous part of modern finance. But settlement is different. It has “same-side” network effects, where having more users of the same technology make that technology more valuable. When there are no existing users of a technology, central banks may be well positioned to provide a kick-start. That is, if central banks move to use new technologies in the settlement systems they operate, they could catalyze adoption across their large networks.

The Federal Reserve System has a long history of leading financial innovation in markets and settlement. For example, in 1962 the Chicago Fed was using computers to automate away the difficulties in handling papers checks. In 1971, the New York Fed computerized its government securities clearing, which connected to all the other Reserve Banks through the Culpeper Switch. Publications at the time acknowledged the role technology could play in better delivering Congress’s directive to improve the nation’s flow of funds. And they were right, because today, the Federal Reserve is still innovating. FedNow launched in 2023 and already has over 600 financial institutions participating.

Central banks have had a lot of experience in coordinating adoption of new technologies since the 1960s. One of the biggest and most successful examples was the global coordination on the adoption of the CLS system (in which the New York Fed played a key role). CLS is a payment system that settles trillions of dollars of foreign exchange (FX) trades every day with a “payment versus payment” (PvP) safety mechanism. This ensures that money movements are orchestrated and avoids settlement risk (the risk that one side delivers and the other does not). It is pivotal for safe settlement, especially in times of market stress. When other financial markets froze following the failure of Lehman Brothers, the FX market functioned properly—and many give CLS the credit.

Yet CLS only exists because central banks pushed for it as part of efforts to remove settlement risk from the vast FX markets since the mid-1970s (following another crisis). After years of coordination among central banks and commercial banks, CLS launched in 2002. And because the change was collaborative, it was also orderly and inclusive—unlike the transition in the 1960s.

The case of CLS is instructive not only in terms of how central banks coordinate technological change, but also with regard to potential requirements for future tokenized systems. It offers two lessons. First, CLS settles with PvP (for securities, the equivalent is “delivery versus payment,” or DvP). Many tokenized systems refer to “atomic settlement,” which performs the same function. Second, CLS has access to central bank money, which reduces credit and liquidity risks. A tokenized system without both of these features may not be as robust as existing systems.

Recent Research and Analysis

In addition to taking lessons from the past, central banks can look forward by using research and experimentation to better understand tokenization’s potential capabilities and limitations. Multiple successful experiments show efficiencies in a completely tokenized world—where money and securities are all tokenized and settlement can be automated and synchronized with smart contracts.

Yet some have argued that real-world adoption is unlikely to see all money and all securities tokenized simultaneously. Change takes time, and there may be a period of years where tokenized money would need to interact with traditional securities, or vice versa. It is also not clear whether money or securities might be tokenized first. While money is simpler and easier to tokenize than complex, data-heavy securities, some researchers argue that managing complexity is where tokenization’s greatest potential benefits are to be found.

Experiments have borne out the difficulty and disappointment of interactions between traditional and tokenized systems. For example, in Switzerland, Project Helvetia initially linked the existing payment system to a tokenized securities system. However, without tokenized cash, the experiment found that operational burdens were added, not reduced. So when the new securities system went live, it did so with tokenized cash it issued itself, backed by funds at the central bank. The Swiss National Bank is also running a pilot that makes tokenized central bank money available for settlement.

The path to any adoption is not clear. Yet if changes do take place, coordination might be prudent. Between 1968 and 1972, Wall Street firms that were slow to change or ineffective in managing their computers ended up failing. Some have warned that similar outcomes could be possible if there is insufficient coordination and oversight among industry and regulators. And any transition to tokenized settlement could be costly.

Conclusion

Central banks can take lessons on technology and change from areas well beyond finance. In 1969, as Wall Street lay buried in paper, Neil Armstrong was stepping onto the moon. Yet, as NASA’s Spinoff magazine shows, space-age technology can take decades to gain widespread adoption. The tokenization experiments being carried out today by central banks are exciting, but may be just one small step.

As history suggests, any giant leap in bringing greater efficiency to financial markets may only come if new technologies clearly outperform existing systems and central banks coordinate efforts to use them. Responsible innovation is collaborative, and so are central banks.

Christopher Desch is an engineer and product architect at the New York Innovation Center at the New York Fed.

Henry Holden is an adviser at the Bank for International Settlements, on secondment with the New York Innovation Center.

The views expressed in this article are those of the contributing authors and do not necessarily reflect the position of the New York Fed or the Federal Reserve System.