Sigurd Ulland

This is the second in an ongoing series on nonbank financial institutions. Read the first article on the basics of NBFIs.

The Federal Reserve has historically relied on commercial banks and select broker-dealers to implement and transmit monetary policy. In recent years, nonbank financial institutions (NBFIs) have taken on increasingly important roles. As discussed in a previous article, NBFIs are financial companies that perform a variety of financial services but do not have a bank license. Examples of NBFIs include investment funds, pension funds, insurers, government-sponsored entities, and broker-dealers. In this article, we discuss some of the ways that NBFIs contribute to the implementation and transmission of monetary policy in the United States.

Nonbank Financial Institutions and Monetary Policy Implementation

First, a brief review of how monetary policy is set and implemented in the U.S.: The Federal Open Market Committee (FOMC or Committee) is responsible for setting the stance of monetary policy—meaning how much it encourages or slows economic growth—to achieve the Fed’s goals of maximum employment, stable prices, and moderate long-term interest rates. The Committee does this primarily by setting a target range for the federal funds rate, a short-term interest rate. Once the FOMC determines the appropriate stance of policy, it issues directives to the Open Market Trading Desk at the New York Fed (the Desk) to implement the policy.

For much of its history, the Desk has implemented monetary policy through transactions with commercial banks and a limited set of broker-dealers, which are NBFIs. These trading counterparties, known as primary dealers, are active market makers in the U.S. Treasury and money markets and meet a range of operational and financial requirements. They support the effective and efficient implementation of monetary policy by participating in open market operations, including the overnight reverse repo facility (ON RRP) and the standing repurchase agreement facility (SRF).

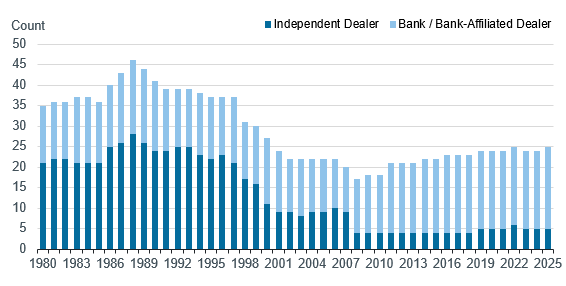

The number of primary dealers has changed over time, peaking at 46 in 1988 before decreasing over the following decade, largely due to industry consolidation. Today, there are 25 primary dealers, of which 80 percent are banks or bank-affiliated broker-dealers and 20 percent are independent broker-dealers. This composition is a notable shift from the 1980s and 1990s when 60 to 65 percent of primary dealers were independent broker-dealers, as seen in the chart below.

Number of Primary Dealers by Type

Source: Federal Reserve Bank of New York

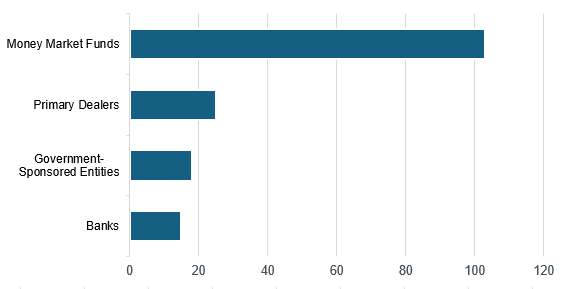

Ahead of the implementation in 2015 of the ON RRP as an additional policy tool to help keep the federal funds rate in the target range set by the FOMC, the New York Fed expanded its counterparties for conducting reverse repo transactions. In addition to primary dealers, counterparties for ON RRP operations include other banks and NBFIs, including money market funds (MMFs) and government-sponsored enterprises (GSEs), such as Fannie Mae, Freddie Mac, Farmer Mac, the Farm Credit System banks, and the Federal Home Loan Banks, as seen in the chart below. Given the role and footprint of these NBFIs in money markets, their addition as ON RRP counterparties bolstered the Fed’s ability to maintain interest rate control. Going forward, changes in market structure and technology may further affect the role of these entities in the implementation of monetary policy.

Number of ON RRP Counterparties by Type

Source: Federal Reserve Bank of New York

Nonbank Financial Institutions and Market Monitoring

The New York Fed’s Trading Desk monitors financial markets to understand monetary policy expectations, policy transmission, and other important financial market developments. It also gathers intelligence from its trading counterparties and other market participants, including NBFIs, such as broker-dealers, principal trading firms, asset managers, hedge funds, insurers, pension funds, endowments, and sovereign wealth funds. Market intelligence can come through direct conversations with market participants and surveys the Desk conducts with primary dealers and other market participants. The New York Fed also sponsors several financial markets groups that have representatives from NBFIs among their members, including the Treasury Market Practices Group, the Foreign Exchange Committee, the Reference Rate Use Committee, and the Investor Advisory Committee on Financial Markets. Gathering the views of market participants through these channels can shed light on how the stance of monetary policy—whether it is stimulating or constraining the labor market and inflation—is affecting credit conditions, investment activities, and asset allocations. Such market intelligence can inform an understanding of how monetary policy is being transmitted into the financial market and ultimately the real economy.

Nonbank Financial Institutions and Monetary Policy Transmission

NBFIs’ credit and investment activities can affect how monetary policy decisions are passed through to the real economy. The list of monetary policy transmission channels identified in economics literature is constantly evolving, making it challenging to identify which channels are at play at any given point in time. Below we explain the role of NBFIs in a couple of monetary policy transmission channels.

The “credit channel” looks at how monetary policy affects the availability and terms of lending by banks and NBFIs, which in turn can affect the economic decisions businesses and households make. Over the last few decades, many NBFIs have joined banks as credit providers across different asset classes, including corporate debt, consumer debt (credit cards, auto loans, student loans), mortgages (residential and commercial), and equipment leasing. When monetary policy is tightened through higher short-term interest rates, banks and NBFIs typically reduce how much credit they extend to businesses and households as the cost of their own funding increases. While this has long played an important role in monetary policy transmission through banks, the growing role of NBFIs as credit providers across many asset classes can magnify the contractionary effect. Many NBFIs may have comparatively less access than banks to alternative funding sources because they tend to be smaller, privately owned, and may lack access to domestic or international capital markets.

On the other hand, in the same environment, certain NBFIs may be able to provide alternatives to bank financing in the capital markets, provided their own funding costs are not constrained by tighter monetary policy and they are not subject to the same regulatory requirements as banks. For example, broker-dealers may help underwrite and market public bond issuances, or institutional investors, such as insurers and pension funds, may provide financing to borrowers through private debt markets.

As another example, the “risk-taking channel” looks at how monetary policy can alter NBFIs’ risk tolerance and perception of risk, thereby affecting their investment decisions. For instance, a policy-driven low-interest-rate environment may reduce the attractiveness of low-risk assets with low returns and lead investors, such as asset managers, insurers, and pensions, to rebalance their portfolios toward riskier assets with potential higher returns. This rebalancing can cause asset prices to adjust with higher-risk assets increasing and low-risk assets decreasing, amplifying monetary policy transmission. Conversely, a policy-driven high-interest-rate environment may reduce investor appetite for riskier assets if traditionally low-risk assets have relatively attractive returns.

Looking at another aspect of the “risk-taking channel”, a policy-driven decline in short-term interest rates increases the value of NBFIs’ collateral and assets, which can then be deployed by NBFIs to increase their leverage and expand their balance sheets through additional investing or lending. Monetary policy transmission is amplified when an increase in this leverage-driven investment activity fuels an increase in asset prices. Conversely, a policy-driven increase in short-term interest rates decreases the value of NBFIs’ collateral and assets, reducing their appetite to take on leverage and expand their balance sheets through investing or lending. This can again amplify monetary policy transmission as a decrease in investment activity leads to a decrease in asset prices.

NBFIs have come to dominate certain financial activities once heavily intermediated by banks. As a result, NBFIs have taken on a larger role as amplifiers and transmitters of monetary policy, offering opportunities for further research.

To Sum Up

The transition over the last several decades from a bank-centric financial system to a more heterogenous one that includes NBFIs taking on different roles and functions has introduced new challenges and opportunities for the efficacy and efficiency of monetary policy. At the New York Fed we maintain a curated selection of research, analysis, and external resources to facilitate broader understanding of these important institutions and their role in and impact on the implementation and transmission of monetary policy.

Update (March 10, 2025): An earlier version of this article implied that the New York Fed expanded its counterparties for conducting reverse repo transactions as part of the development of the ON RRP facility. In fact, the New York Fed initiated the expansion of its reverse repo counterparties before development of the ON RRP facility began.

Sigurd Ulland is a policy and market analysis advisor in the New York Fed’s Markets Group.

The views expressed in this article are those of the contributing authors and do not necessarily reflect the position of the New York Fed or the Federal Reserve System.