Repurchase and reverse repurchase operations—or “repo and reverse repo” transactions—are critical to the Federal Reserve’s implementation of monetary policy. Alongside a broader suite of open market operations, these transactions influence interest rates and support smooth market functioning by helping to maintain the federal funds rate well within the target range set by the Federal Open Market Committee.

In a repo transaction, a counterparty sells securities to the Fed with an agreement to repurchase the securities at a specified price on a later date. This temporarily increases liquidity in the banking system. Conversely, in a reverse repo transaction, the Fed sells securities to a counterparty with an agreement to repurchase the securities at a specified price on a later date, temporarily reducing liquidity in the banking system.

Over time, the Fed’s approach to monetary policy implementation has evolved, influencing how repo and reverse repo operations are structured and improving the Fed’s ability to support a changing financial system. The current approach addresses the needs of today’s banking system, including its variable and larger liquidity demands, and provides the Fed with greater flexibility in managing its balance sheet.

In this article, we discuss the evolution of repo and reverse repo operations from before the global financial crisis to 2015, a time when the Fed adjusted how it achieves interest rate control. A subsequent article will discuss repo and reverse repo operations from 2015 to the present day.

Before the Global Financial Crisis

Before the global financial crisis, there was limited excess liquidity in the financial system. The Fed operated in what is known as a scarce reserves regime, in which there was a point target for the federal funds rate and few reserves—or money that banks hold at the Fed—beyond those mandated by the Fed. This required the Fed to actively manage its balance sheet using repo and reverse repo operations on a daily basis to maintain rate control and avoid significant volatility.

At the time, the Fed was not permitted to pay interest on reserves, so banks had a significant incentive to reduce their reserve holdings to the minimal required level. Thus, banks with extra reserves were willing to lend to banks that were short. Banks also managed to an average level of reserves, some days reducing their reserves to minimize the costs of holding cash and other days building them up to avoid penalties from insufficient balances.

The Fed’s outright purchases of U.S. Treasuries conducted in the secondary market provided most of the liquidity to the banking system. This accommodated trend growth in more predictable Fed liabilities such as U.S. currency in circulation. However, these purchases were less suitable to meeting short-term fluctuations in other Federal Reserve liabilities as well as reserve demand. The high-frequency variability was addressed by reserve-adding repos and, less frequently, with reserve-reducing reverse repos.

Typically, the goal of these operations was to add a fixed quantity of reserves based on reserve supply-demand projections to ensure money market rates, on average, would clear near the target rate. Most operations were early-morning, fixed-quantity repo operations. The Fed temporarily bought a specific amount of Treasury securities and credited an equivalent amount of cash to primary dealers, which were the main repo market participants at the time. The funds were then redistributed throughout the financial system as needed. These daily transactions brought reserve supply temporarily in line with reserve demand at or near the target federal funds rate.

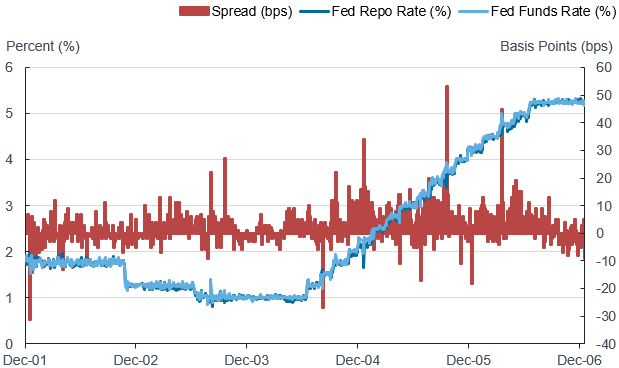

Spread Between Fed Repo Operation Rates and Federal Funds Rate

Most days, the effective federal funds rate—an index calculated daily by the New York Fed based on individual federal funds transactions—printed within a few basis points of the target rate, as shown in red in the chart above. However, rates tended to spike on days when banks’ payment flows were more unpredictable or when they encountered payment delays.

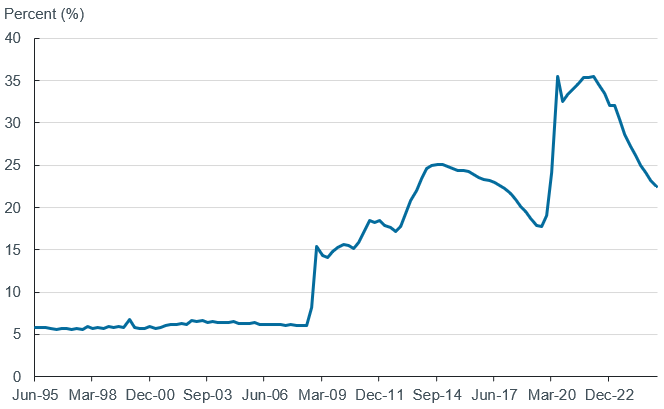

Throughout this time, the Fed’s balance sheet rose largely in line with the growth in currency and the banking system. Reserves and the overall Fed balance sheet were small relative to the economy, as shown in the chart below. Such a framework required precise, daily forecasts of both bank demand for reserves and changes in other non-reserve Fed liabilities.

Federal Reserve Assets as Share of U.S. GDP

The Global Financial Crisis and the Introduction of Interest on Reserves

The global financial crisis created tremendous stress on financial markets, the banking system, and the economy—and as a result, led to a pivotal period for the implementation of monetary policy. The Fed stepped in to stabilize financial markets by reducing interest rates, providing additional liquidity facilities, and engaging in large-scale asset purchases. As it did, however, it became clear that the Fed needed a different way to maintain rate control.

In response to early strains in financial markets, the Fed introduced liquidity facilities in December 2007 and March 2008. To offset the impact on short-term rates, the liquidity created was drained from the financial system in various ways. While these actions allowed the Fed to maintain rate control in a scarce reserves regime, they presented meaningful constraints on its ability to respond to the crisis.

Starting in the fall of 2008, as the crisis intensified, the Fed began to rapidly reduce interest rates. It also expanded its balance sheet through additional liquidity facilities and large-scale asset purchases that were designed to support the financial system and the broader economy. These measures injected substantial amounts of liquidity into the financial system. But they made controlling short-term rates quite difficult, and short-term rates dropped well below the target rate.

Consequently, Congress moved up the date on which the Fed could start to pay interest on reserves, which incentivized banks to hold on to reserves in excess of Fed-mandated requirements. Two different rates were paid on required reserves and excess reserves. When the Fed brought reserve requirements to zero (discussed in the following article), the term shifted to interest on reserve balances. For the remainder of this article, it is referred to as interest on reserves (IOR).

IOR was designed to improve efficiency in the banking system. It also removed what banks viewed as a tax because they had been forced to forgo potential interest income by holding uncompensated required balances at the Fed. In addition, since banks are largely unwilling to lend at rates below what they can earn on their reserves at the Fed, IOR acted as a fairly firm floor on the federal funds and other short-term interest rates for those eligible to earn it. That, in turn, allowed the Fed to continue effectively controlling the federal funds rate even in the presence of substantially higher levels of liquidity in the banking system.

Post-Crisis System and Introduction of the Overnight Reverse Repo Facility

By December 2008, the substantial increase in liquidity had significantly compromised the Fed’s ability to precisely manage the federal funds rate with existing tools. As it brought the federal funds rate to near zero, the Fed formally adopted a target range for the federal funds rate, replacing the prior point target. Nonetheless, the federal funds rate and other money market rates started to trade somewhat below IOR. This was due largely to nonbank financial institutions (NBFIs) that were not eligible to earn IOR and thus were willing to lend cash at lower rates. In order to provide a firmer floor on rates, the Fed first tested and then, in December 2015, formally introduced the Overnight Reverse Repurchase Agreement (ON RRP) facility.

The ON RRP was, and still is, structured differently from the repo and reverse repo operations conducted before the crisis. Previously, unscheduled, competitive-rate, fixed-quantity auctions were conducted with primary dealers only. In contrast, ON RRP is a standing, fixed-rate, variable-quantity operation conducted with a broader set of counterparties. The facility works with IOR to set a firmer floor on overnight interest rates by providing the largest cash holders, including NBFIs like money market funds and government-sponsored enterprises, with an alternative investment option and thus a greater ability to negotiate rates above the facility rate in the private market. The ON RRP can also allow some reserves, which banks may not want to hold, to transform into non-reserve liabilities, expanding the range of entities holding Fed liabilities.

Repo and Reverse Repo Operations Across Time

| Period | Structure/Type | Pricing | Reserves Environment | Purpose |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Prior to 2007-2009 Global Financial Crisis | Fixed-quantity repo | Variable rate | Scarce | Temporarily add a fixed quantity of reserves to bring reserve demand in line with supply at/near the target rate for the federal funds rate |

| 2015-Present | Variable-quantity standing reverse repo (Overnight Reverse Repo Facility) | Fixed rate below IOR | Ample to abundant | Remove as many reserves as desired by financial system, place a firmer floor on federal funds, other money market rates |

| 2019-2020* | Variable-quantity repo with fixed maximum size | Variable rate with fixed minimum bid rate near IOR | Ample to abundant | Provide as many reserves as demanded by financial system to bring rates closer to administered rates (2019) or address broader market functioning (2020) |

| 2021-Present* | Variable-quantity standing repo with fixed maximum size (Standing Repo Facility) | Effectively fixed rate with fixed minimum bid rate above IOR | Ample to abundant | Limit upward pressure on repo market rates which may transmit to federal funds rates |

Concluding Reflections

Over time, the Fed has adjusted the level of liquidity it provides the financial system in response to economic and market conditions. It has also modified how open market operations are used to maintain control of the federal funds rate. Until 2008, the New York Fed’s Trading Desk targeted the federal funds rate by leaving a structural reserves deficit and conducting competitive fixed-quantity repo operations to provide just enough reserves to satisfy demand at the target rate. As liquidity increased, IOR, in combination with the ON RRP, allowed the Fed to maintain strong rate control amid abundant liquidity.

In the next article, we discuss the formal adoption of the ample reserves regime and how this altered repo and reverse repo operations. We also explore how those operations helped address the repo market stress in September 2019 and the extraordinary market dislocations at the onset of the COVID-19 pandemic in March 2020.

Kevin Clark is a principal in the New York Fed’s Markets Group.

Dina Marchioni is a director in the New York Fed’s Markets Group.

Julie Remache is the Deputy Manager of the System Open Market Account and a senior leader in the New York Fed’s Markets Group.

Will Riordan is an advisor in the New York Fed’s Markets Group.

Also in this series:

The views expressed in this article are those of the contributing authors and do not necessarily reflect the position of the New York Fed or the Federal Reserve System.