In a prior article, we discussed the scarce reserves regime the Fed used to implement monetary policy before the global financial crisis, and how the Fed’s repo and reverse repo operations evolved in response to the crisis. In this article, we explore the continued evolution of repo and reverse repo operations—namely, how they were structured to address the spike in repo rates in September 2019 and the extraordinary market dislocations at the onset of the COVID-19 pandemic in March 2020.

Rate Liftoff, Balance Sheet Runoff, and Adoption of Ample Reserves Regime

After the global financial crisis of 2007-09, it took several years for the unemployment rate to come down from its peak and for the economy to fully recover. Over this time, the Fed gradually increased policy rates and reduced the liquidity in the financial system. As it did, the Fed’s framework to implement monetary policy continued to evolve.

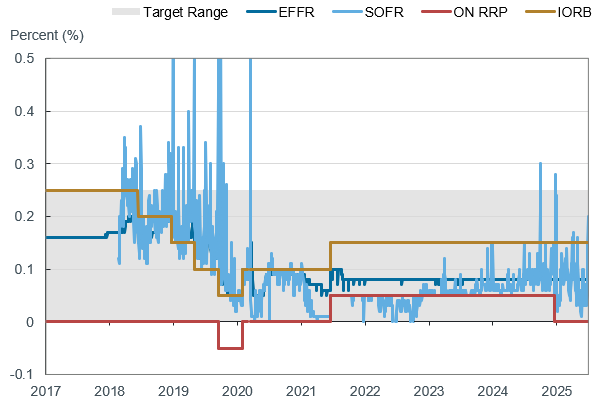

In December 2015, after considerable improvement in the labor market, the Fed began to raise the target range for the federal funds rate from zero. It did so by raising administered rates—the interest rate on reserves (IOR) and the Overnight Reverse Repurchase Agreement (ON RRP) rate—which together proved effective at influencing rates amid an abundance of liquidity. The federal funds and other money market rates moved largely in lockstep with changes in the administered rates and the target range.

Beginning in October 2017, the Fed began to reduce its holdings of securities purchased through large-scale asset purchases, which simultaneously reduced the level of reserves and other forms of liquidity. With less liquidity in the financial system, money market rates slowly began to move higher within the Fed’s target range, and as widely expected, usage of the ON RRP quickly declined to near zero.

In January 2019, the Fed formally adopted the ample reserves regime, which, de facto, had been in place since the global financial crisis. In this policy framework, the Fed supplies enough reserves to the financial system, so that rate control is implemented using administered rates rather than the active management of reserve balances, as was done in the pre-crisis scarce reserves regime. In an ample reserves regime, changes in reserve balances result in only modest movement in the federal funds and other short-term interest rates. In contrast, an abundant reserves regime can result in no movement in rates, while a scarce reserves regime can lead to much larger, more volatile movements. Since reserve requirements are not necessary to drive demand for reserves in an ample reserves regime, the Fed subsequently set reserve requirements to zero.

Repo and Reverse Repo Operations Across Time

| Period | Structure/Type | Pricing | Reserves Environment | Purpose |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Prior to 2007-2009 Global Financial Crisis* | Fixed-quantity repo | Variable rate | Scarce | Temporarily add a fixed quantity of reserves to bring reserve demand in line with supply at/near the target rate for the federal funds rate |

| 2015-Present* | Variable-quantity standing reverse repo (Overnight Reverse Repo Facility) | Fixed rate below IOR | Ample to abundant | Remove as many reserves as desired by financial system, place a firmer floor on federal funds, other money market rates |

| 2019-2020 | Variable-quantity repo with fixed maximum size | Variable rate with fixed minimum bid rate near IOR | Ample to abundant | Provide as many reserves as demanded by financial system to bring rates closer to administered rates (2019) or address broader market functioning (2020) |

| 2021-Present | Variable-quantity standing repo with fixed maximum size (Standing Repo Facility) | Effectively fixed rate with fixed minimum bid rate above IOR | Ample to abundant | Limit upward pressure on repo market rates which may transmit to federal funds rates |

The ample reserves regime has been both effective and efficient, providing strong rate control without the need for frequent close management and forecasting of Fed liabilities. Because there are fewer limits on their size and variability, these liabilities are substantially more volatile now compared to the pre-crisis period. The use of administered rates also divorces rate control from the size of the Fed’s balance sheet, meaning the Fed can adjust its balance sheet to support the broader economy without adversely affecting rate control.

September 2019 Repo Events and the March 2020 ‘Dash-for-Cash’

By the second half of 2019, Fed securities holdings and reserve balances had been reduced substantially. As seen in the chart below, money market rates were notably higher within the target range, with the federal funds and repo rates at or just above IOR. In mid-September 2019, the repo market experienced severe dislocations amid a sharp temporary decline in reserves, substantial Treasury securities settlements, and a corporate tax date, causing a spike in repo rates. To keep the federal funds rate within its target range, the Fed introduced a series of morning liquidity-adding repo operations followed by Treasury bill purchases to bring reserves back up to ample levels. The large overnight and term repo operations were priced competitively, with a fixed minimum bid rate near IOR, consistent with the Fed’s goal to return and maintain reserves at ample levels and bring market rates closer to administered rates. These operations with primary dealers were in place through the beginning of 2020.

Administered and Reference Rates, Spread to Bottom of Target Range

In March 2020, in response to the pandemic and the global “dash-for-cash,” the Fed introduced a wide range of emergency lending facilities, a series of asset purchases, and further repo operations to support market functioning. These repos were similar to those used in response to the 2019 market dislocations: They were frequent, offered in large sizes, and priced close to market rates to ensure sufficient liquidity in the banking system. The repos were further calibrated to respond to the crisis, with an additional afternoon repo offering of up to $500 billion and a lengthening of term repo tenors.

These operations initially saw substantial usage, followed by a rapid decline to zero as the broad policy response restored market functioning, pushed reserves to abundant levels, and caused money market rates to decrease relative to the administered rates. As usage fell in mid-2020, the repo operation offering rates were raised to levels modestly above market rates to shift them to a backstop position. This helped contain occasional, unexpected upward pressure on the federal funds and other money market rates, and it encouraged greater private-market activity.

The Standing Repo Facility

In July 2021, these repo operations were formalized and transitioned to a daily standing operation known as the Standing Repo Facility (SRF). The SRF is intended to support effective implementation of monetary policy and smooth market functioning by limiting upward pressure in portions of the repo market which could then push the federal funds rate higher. The facility rate is currently set at the top of the target range and above market rates. Usage is thus expected to be infrequent, though counterparties are expected and encouraged to make use of the facility when it’s economically attractive. The SRF is currently structured as daily auctions both in the morning, offering liquidity early when the market is most liquid, and in the afternoon, when fewer options exist.

In addition to the Fed’s primary dealers, a subset of U.S. banks are counterparties to the SRF, allowing them to monetize Treasury, agency debt, and agency mortgage-backed securities on a temporary basis. Similar to other iterations of repo operations, the SRF is structured and priced to implement monetary policy effectively—in this case for an ample reserves regime that is still susceptible to unexpected increases in demand for liquidity.

Looking Ahead

In 2022, the Federal Open Market Committee announced it intended “to slow and then stop the decline in the size of the balance sheet when reserve balances are somewhat above the level it judges to be consistent with ample reserves.” Since then, the Fed has twice slowed runoff, allowing reserves to approach the ample level gradually and predictably. Thus far, a wide range of measures indicate reserves remain abundant. The ON RRP continues to see declining usage as runoff continues, and the SRF remains positioned to minimize occasional upward pressures in money market rates.

The Fed is currently committed to operating in an ample reserves regime, and repo and reverse repo operations are expected to play an important role in helping to achieve rate control. As always, the Fed can adjust the structure and pricing of these and other open market operations to support its goals.

Kevin Clark is a principal in the New York Fed’s Markets Group.

Dina Marchioni is a director in the New York Fed’s Markets Group.

Julie Remache is the Deputy Manager of the System Open Market Account and a senior leader in the New York Fed’s Markets Group.

Will Riordan is an advisor in the New York Fed’s Markets Group.

Also in this series:

The views expressed in this article are those of the contributing authors and do not necessarily reflect the position of the New York Fed or the Federal Reserve System.