Germaine Simonson owns Rocky Ridge Gas + Market in Arizona’s Navajo Nation. It’s one of three businesses she operates. (Photo: Raymond M Chee Jr.)

This story explores the experience of a small minority business owner in Arizona’s Navajo Nation who worked with a community-based lender to obtain Paycheck Protection Program loans that helped her pay the employees of her three businesses during the COVID-19 shutdown. It is the fourth in a series published by the New York Fed on behalf of Fed Communities, a project that connects the Fed’s data, tools, and expertise with communities and those who serve them.

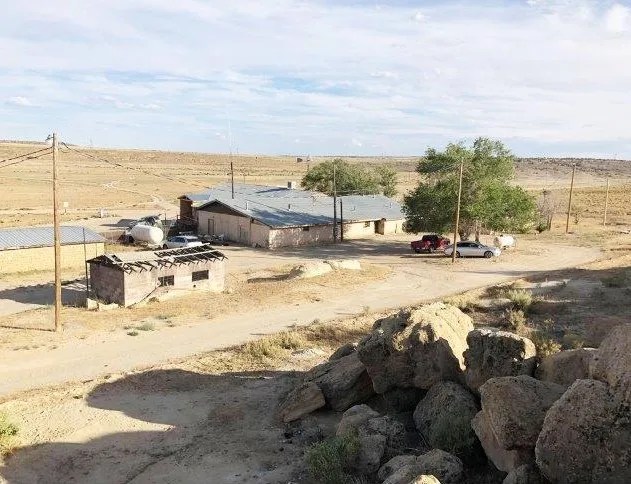

Rocky Ridge Gas + Market doesn’t have an address — not a number, not a street name. Instead, those headed for it are told it’s one mile south of Rocky Ridge Boarding School in Navajo Nation down a dirt road, the one that curves around the market’s lone gas pump before continuing across brown and barren land.

Even before the COVID-19 pandemic made it difficult for stores to stock toilet paper and disinfectant, the market’s owner and a member of the tribe, Germaine Simonson, faced supply-chain challenges. Because her northern Arizona store is out of the way and its orders are small, not many distributors travel to her with the goods she needs. She has to meet one supplier in a city 50 miles away, and she also shops at Sam’s Club in Flagstaff, Arizona, two hours away. That city is also where her bank and bookkeeper are.

Shoppers cleared the shelves at Rocky Ridge Gas + Market of goods including canned items, paper products, and dried goods during the first weeks of the COVID-19 pandemic.

“I’m really a fish with very little water out here,” says Simonson, who grew up on this tribal land, left it to attend high school and college, and returned here, where she’s built a home and three businesses. “Half the time, I’m flip-flopping around because I don’t have a lot of the resources I need to run at the level I should run.”

The pandemic left her more parched than ever: For a while, the distributor who delivers her supplies ran out of the very things people were told would keep them safer. At the same time, shoppers cleared her shelves of canned items, paper products, and dried goods. And she wasn’t traveling as much from Hardrock, Arizona, to Flagstaff for the same reason others stayed in: the coronavirus. So for weeks her shelves were bare of certain items, including hand sanitizer and disinfectant wipes, a particularly unhelpful situation for an area where quite a few people live without running water or are urged to conserve water and at a time when frequent handwashing is advised.

The Rocky Ridge market draws its name from the rocky ridge behind it, owner Germaine Simonson says.

Simonson reduced hours and, following the Navajo Nation’s orders, closed on weekends, which is normally when workers who live off the reservation during the workweek shop. Unfortunately, after being allowed to reopen for three weekends, Simonson expected another shutdown to begin in late September, leaving her concerned about covering the market’s expenses, not to mention making money. COVID-19 also cancelled family gatherings and tribal ceremonies, which draw crowds to the area. Serendipitously, it turns out, Simonson had started an online service in late 2019 that allowed people anywhere to have “Grandma Baskets” delivered to people living on the reservation, and the service really took off after the pandemic spread. That absolutely helped her store, she says.

Another of her businesses, though, was essentially stopped in its tracks: Turquoise Trail Transport provides nonemergency medical transport, and when nonemergency and elective medical visits were curtailed, the business that makes her family of five the most money was reduced by roughly 75 percent. (She and her husband have three children, ages 25, 16, and 14.) Simonson cut hours for her office assistant, and her drivers spent months splitting the work that remained, with their availability dependent on each of their comfort levels. She knows their work carries greater risk of exposure.

“I don’t want anybody losing their life over work that has to be done for any of my businesses — it’s not worth it,” she says. “They always have the ability to say no. They also need to work and make money. I don’t know when we will be back to full transporting. Even though they say Arizona’s opened back up for business, hospitals have not.” Things remained slow as of late September.

Simonson needed help, and a lender she discovered through a Native American women’s entrepreneur group on Facebook led her to it.

A banker with Rural Community Assistance Corporation, or RCAC, quickly provided Simonson with an application for the Paycheck Protection Program (PPP), the program offered through the U.S. Small Business Administration (SBA) that provided loans — forgivable under certain conditions — to businesses impacted by the pandemic. In about a business week, she learned she’d qualified for three PPP loans (the last for her sole-proprietorship consulting business). Their amounts were $1,500, $5,000, and $15,000, the largest for Turquoise Trail Transport.

“I was shocked — really? Really?” she remembers. “I was celebrating all the way around. It was such a relief. I was very happy to continue to pay our staff,” including her office assistant, who was brought back on full-time. Simonson has also used the PPP dollars to keep the market’s refrigerators humming. “Just because my store hours are reduced doesn’t mean my utility costs are reduced,” she notes. “Machines have to keep going.

“PPP funding took away the stress for weeks — months,” Simonson continues. “But the stress is going to return when the PPP funds run out. I’ll be forced to make some decisions here in the next two to three weeks if no other relief comes through.”

That was late July. The next month, though, Turquoise Trail Transport picked up some new business taking members of the tribe to get medical care off the reservation because local facilities remained shut. That has kept her business afloat and its employees behind the wheel.

Helicopters and Help to Rural America

RCAC sure earns the “rural” in its name. A community development financial institution (CDFI) based in West Sacramento, California, RCAC serves some communities so remote its staff must travel several hours from an airport to a place with lodging and then on from there because lodging isn’t available where they’re headed. To get to at least one spot in Alaska, its people fly commercial, then board a smaller plane or — if it’s snowing — a snowmobile. Navajo Nation is only one of the tribal places RCAC serves; at times, its staffers have ridden by helicopter or mule to reach the Havasupai at the Grand Canyon’s bottom.

It is across 13 western states that RCAC finances affordable housing projects, community facilities such as hospitals, environmental infrastructure projects, and small businesses. Its rural work is well known, and RCAC was asked by community partners to plead for federal funds on behalf of rural America when the pandemic threatened and shut down economies. It was when its staff spent one week mailing more than 20 letters to senators asking for funding that it really hit Dawn VanDyke, the CDFI’s communication manager: This is serious. (RCAC usually signs to support others’ letters more than it sends individual ones, she explains.)

Dawn VanDyke, RCAC

Even before COVID-19, because of the remoteness of the areas it serves, RCAC’s field staff worked from home offices closer to those places. The pandemic meant staffers needed to navigate the new risks of travel, and all of RCAC’s 70 corporate office employees, within a matter of days, had to figure out how they would, from their homes, be a lifeline for small businesses in remote corners of the West.

Like other small lenders, RCAC provided only limited lending during the PPP’s first, short-lived round in early April: It made 11 loans totaling roughly $855,000. Also, like other small lenders, it lent many times those amounts during the PPP’s second round: This time it made 98 loans totaling more than $9.3 million. Twenty-one percent of the lending went to Native communities, and 47 percent reached counties with persistent poverty. To find businesses in need, RCAC first told its existing borrowers and clients that it was able and ready to make PPP loans. Then it notified partners that it would work to help their clients, from entrepreneurs to nonprofits.

As part of its work in very remote areas, Rural Community Assistance Corporation lends or gives grants to help people repair septic or well systems. Pictured here is a water system in Arizona.

Not every business owner wanted to apply, though. For Juanita Hallstrom, RCAC’s loan fund director, one woman’s story sticks with her. The woman leads an organization serving Native Hawaiians, and the organization has long been an RCAC client. She was worried she’d be unable to pay the employees of her nonprofit in the Hawaiian Islands, but she figured the PPP was too good to be true, especially for people of color. Many of the small-business owners RCAC met reported having been turned away by other financial institutions for a variety of reasons, Hallstrom explains, and that bred skepticism. RCAC staff insisted it was possible to help the nonprofit leader in Hawaii with her payroll and encouraged her to apply. Her PPP loan was approved in under three days.

Juanita Hallstrom, RCAC

“She was in tears because she could not believe it. ‘I didn’t want to apply,’” Hallstrom recalls the woman telling her. “‘I just didn’t think it was going to be available to me. What you’ve done for us proves to me that organizations like yours do support communities in a way that maybe other financial institutions do not.’” A weight off her shoulders, the woman took to telling other Hawaiian organizations to call RCAC and that “really, this is available.”

PPP, though, wasn’t in reach for all small-business owners struggling to survive in the Navajo Nation, Simonson notes. She knows some who couldn’t clear the PPP finish line because their financials, such as tax records, weren’t up to date or complete. “I knew a lot of my colleagues were not going to be able to get this,” she says. “PPP was a real simple process — as long as your financials were up to date. We don’t have easy access to bookkeepers and accountants; our financials are behind. That’s something I want policymakers to know.”

Simonson hopes more help is on its way. Some of her friends’ businesses that operate in larger Arizona cities, such as Mesa and Phoenix, have received relief through their local municipalities. Local support hadn’t been offered by the Navajo Nation as of her July interview, but months later, the tribe did announce new relief grants for businesses and artisans, and Simonson was studying in late September whether she’s eligible to apply. She continues to urge the tribe to do more to help its business owners, for example, by allowing them to skip paying taxes so they may have more money for responding to COVID-19.

To get to at least one rural place they serve in Alaska, Rural Community Assistance Corporation staffers fly a smaller plane.

It’s about Community, Not Competition

Hallstrom doesn’t know the reasons why so many of her small-business customers were turned away when they sought PPP loans. She’s heard some were told institutions weren’t offering them or had run out of PPP funding. If her contacts are any indication, it’s clear many small businesses weren’t served promptly or at all. RCAC, meanwhile, kept lending PPP and other loans, growing the loans on its books tremendously in a short period of time and serving many new borrowers. “One of the biggest differences between this and the Great Recession is how much our funders have stepped up for us and helped us with capital,” says Julia Helmreich, RCAC director of communication, development, and events.

CDFIs use capital they generate themselves and the capital of others to make loans. Back in 2007–2009, when many banks were strapped during the financial crisis and recession, RCAC received less capital from other funders. This year, in contrast, as the pandemic spread to the United States, banks and foundations familiar with RCAC extended $11 million to it to keep it lending. “It was the first time that, wow, everybody’s reaching out to us,” Hallstrom says. “I’ve been here 20 years, and this pandemic brought us — banks, foundations, and RCAC — closer together. It wasn’t about competition of dollars. It was more about caring for our communities.”

As of late September, RCAC had submitted the paperwork for 13 borrowers to have their PPP loans forgiven; it was too soon after their submissions to expect a response from the SBA just yet. The focus going forward will be on constant communication with those who received the loans — reminding them of the amount of time they have left to submit for loan forgiveness, letting them know RCAC staffers are ready to assist, Hallstrom says. “This has been traumatic. We’re all working in an environment we’ve never experienced before,” she adds. Given that, RCAC wants to make filing as easy as possible on borrowers.

RCAC will build from its new and strengthened relationships with other institutions to continue to coordinate with each other and help communities survive the lasting challenges of COVID-19. One thing’s for sure, Helmreich says: Small businesses will need more money to stock supplies and buy equipment necessary to do business in this changed environment, and small lenders like RCAC will continue to need more — and affordable — capital to meet that need.

The Federal Reserve System is working to support small lenders and small businesses during the COVID-19 pandemic (the Cleveland Fed has infographics that explain how in plain English). For more about the Fed’s work on small businesses, including access to credit, see Fed Small Business and the Federal Reserve COVID-19 CDFI Survey.

Want to be among the first to see other stories in this series and more content like this going forward? Sign up for the Fed Communities mailing list.

This article was originally published by the New York Fed on Medium.

The views expressed in this post are those of the interviewees and contributing author and do not necessarily reflect the position of the Cleveland Fed, the New York Fed, or the Federal Reserve System.