The Federal Home Loan Bank (FHLB) system was created almost a century ago and has evolved over time to play an important role in monetary policy implementation. It is a key participant in money markets, providing liquidity to thousands of financial institutions in the U.S. This article looks at why this system was created, how it is structured, and the composition of its balance sheet.

What Is the FHLB System?

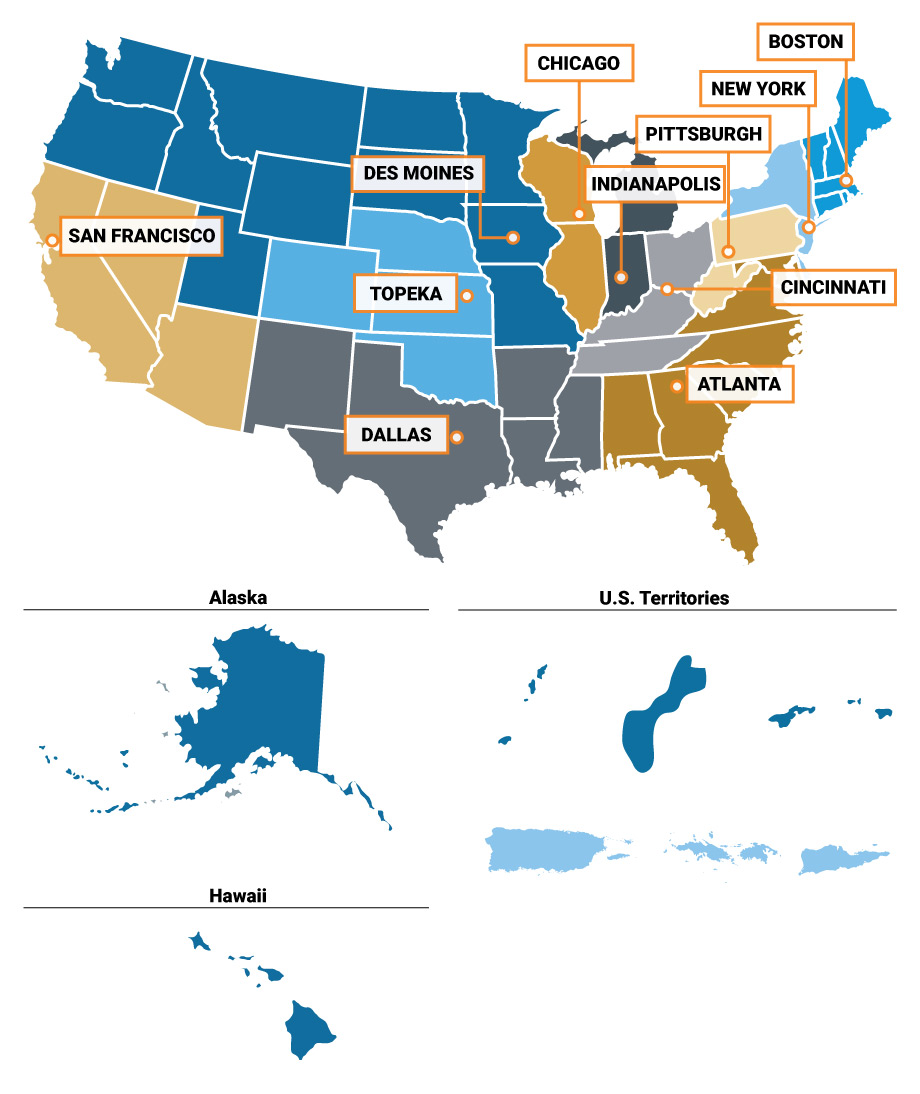

The FHLB system currently consists of 11 institutions—each of which operates within a defined geographic area or district, as shown on the map below—and an Office of Finance that acts as the system’s fiscal agent. Collectively, they constitute one government-sponsored enterprise (GSE), which was established by Congress in 1932 through the Federal Home Loan Bank Act for the purpose of supporting the liquidity needs of residential mortgage lenders during the Great Depression. Since then, Congress has modified the FHLB system on several occasions, including following the savings and loan crisis of the 1980s, the 1986-1992 commercial banking crisis, and the 2008 mortgage crisis. The FHLB system is supervised and regulated by the Federal Housing Finance Agency, an independent agency established by the Housing and Economic Recovery Act of 2008.

Eligible Institutions May Become Members in Their District Federal Home Loan Bank

Each of the 11 FHLBs is a federally chartered cooperative financial institution, owned and capitalized by its members. Originally, FHLB membership was limited to savings and loan associations (also known as thrifts) and certain insurance companies. Toward the end of the 1980s, membership was expanded to domestically chartered commercial banks and credit unions. Today, most of the roughly 6,500 FHLB members are commercial banks (55%), followed by credit unions (26%), insurance companies (10%), thrift institutions (8%), and community development financial institutions (1%).

An eligible financial institution may become a member of the FHLB that serves the district that includes the institution’s principal place of business. For financial holding companies with subsidiaries, each eligible subsidiary may become a member of the FHLB in the district in which it is situated. Once an institution becomes a member, it must purchase and maintain a minimum capital stock investment in its FHLB, which varies by district. In addition, prior to applying for a loan, members must acquire activity-based FHLB stock proportional to the size of the loan. Over the last two and a half decades, the FHLB system’s capital has ranged from 3.5% to 7% of assets.

What Types of Assets Do FHLBs Hold?

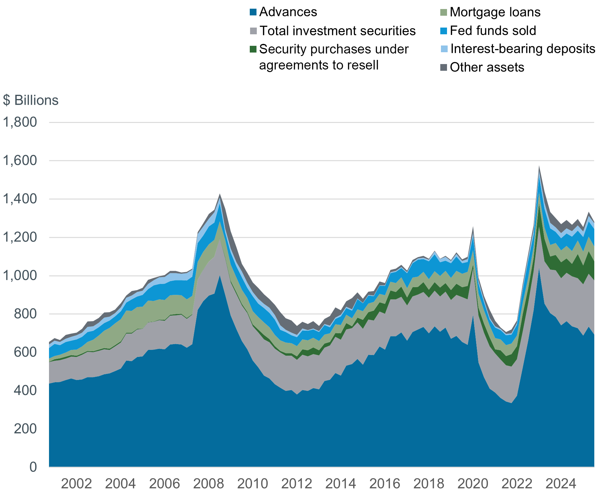

The FHLB system was created to provide a source of liquidity for its members paralleling the access to the Federal Reserve’s discount window that only commercial banks had at the time. Today, providing liquidity to their members—via collateralized loans known as advances—remains a central function of the FHLBs. Over the past 25 years, advances have represented around 60% of FHLB assets on average, ranging from 47% in the fourth quarter of 2021 to 70% in the fall of 2008. In the third quarter of 2025, the 11 FHLBs held nearly $700 billion in advances, or 54% of their total assets. Advances are overcollateralized; that is, the value of the collateral pledged must exceed the size of the advance, protecting FHLBs against credit losses on advances. In the event a member fails and is placed in receivership or conservatorship, FHLBs are further protected by their super lien authority that gives them priority on pledged collateral over the claims and rights of a receiver or conservator such as the Federal Deposit Insurance Corporation (FDIC).*

Beyond supporting mortgage lending, the FHLBs provide a key source of liquidity during periods of financial stress. As the chart below shows, advances grew steadily in the second half of 2007 and into 2008, in early 2020, and from 2022 into the first quarter of 2023—at the onset of the Global Financial Crisis, the COVID pandemic, and the March 2023 banking stress, respectively.

FHLB Assets: Advances Adjust to Meet Members’ Funding Needs

In terms of assets other than advances, FHLBs face limitations on investments, including restrictions on trading securities for speculative purposes, market-making activities, and investing in non-investment-grade debt securities. They invest in mortgages (6% of assets as of the third quarter of 2025) and some debt securities (22% of assets), including mortgage-backed securities (MBS) issued by Freddie Mac and Fannie Mae, securities issued by the U.S. government and its agencies, and certain private-label MBS.

Additionally, FHLBs hold a portfolio of cash-like assets—interest bearing deposits, reverse repos, and federal funds sold—that currently amounts to around 17% of their assets. While federal funds sold represent only 7% of FHLB assets, FHLBs play a key role in the federal funds market, which is central to the Federal Open Market Committee’s (FOMC) communication of the stance of monetary policy. As discussed in this post, FHLBs account for more than 90% of federal funds sold each day.

Consequently, the rates that FHLBs are willing to accept when selling federal funds greatly influence the distribution of rates on federal funds trades. Their willingness to sell federal funds can be influenced through the Federal Reserve’s monetary policy tools, in particular the overnight reverse repo facility (ON RRP). While FHLBs are ineligible to earn interest on balances in their accounts at the Federal Reserve, all 11 are counterparties to the ON RRP. The ON RRP provides an “outside investment option” to FHLBs that incentivizes them to lend at rates weakly above the ON RRP rate, helping to keep the federal funds rate within the FOMC’s target range.

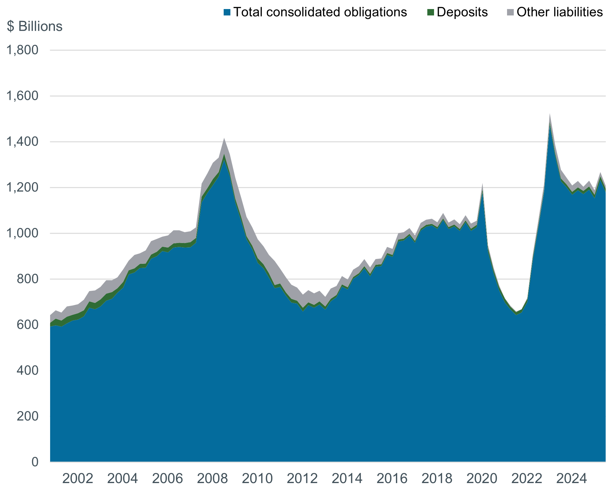

What Types of Liabilities Do FHLBs Hold?

To provide funding to their members, FHLBs issue debt securities. Debt issuance is coordinated by the Office of Finance on behalf of the FHLB system. Although each FHLB is a separate corporate entity, the 11 FHLBs are jointly and severally liable for the securities issued by the Office of Finance. The FHLB system’s GSE status provides an implicit federal guarantee, which allows the FHLB system to borrow at rates close to Treasury rates and, in turn, offer advances at relatively favorable rates to their members. As the chart below shows, bonds and discount notes, which the FHLBs refer to collectively as consolidated obligations, constitute the vast majority of FHLB liabilities, accounting for 94% of FHLB liabilities on average since 2001. In the third quarter of 2025, consolidated obligations reached nearly $1.2 trillion, and almost 70% of these obligations were bonds. Of the $190 billion in bonds the Office of Finance issued during this period, about 70% had maturities of a year or less, and less than 10% of the issuance had maturities exceeding three years.

FHLB Liabilities: Debt Securities Are FHLBs’ Main Liabilities

Conclusion

The FHLB system’s structure and footprint have evolved since its inception in the 1930s as the financial system in the U.S. has developed. In supporting their members through advances, FHLBs not only have become key participants as cash lenders in money markets, such as the federal funds market, but also as borrowers from money market funds in short-term debt markets. This dual role of the FHLBs therefore makes the FHLB system a key participant in monetary policy implementation in the U.S.

* Correction (November 25, 2025): An earlier version of this article incorrectly described the super lien authority of FHLBs. Super lien authority gives FHLBs priority over receivers and conservators such as the FDIC on pledged collateral in the event a member fails and is placed in receivership or conservatorship.

Gara Afonso is a financial research advisor in Money and Payments Studies in the Research and Statistics Group at the New York Fed.

Gonzalo Cisternas is a financial research advisor in Money and Payments Studies in the Research and Statistics Group at the New York Fed.

Will Riordan is a capital markets trading advisor in the Markets Group at the New York Fed.

The views expressed in this article are those of the contributing authors and do not necessarily reflect the position of the New York Fed or the Federal Reserve System.