LIBOR is often dubbed “the world’s most important number” and you’ve likely heard about widespread manipulation of the benchmark rate that resulted in significant fines for some banks.

Despite being aware of this history, few people understand LIBOR’s wide-reaching role in the financial system, why efforts are underway to move to a different benchmark rate, and how the New York Fed is involved. Here are some of your burning questions answered, including those on the alphabet soup of terms related to this work — LIBOR, the ARRC, SOFR — and more.

1. What is LIBOR anyway and what’s wrong with it?

The London Interbank Offered Rate is the underlying interest rate used in many financial instruments and contracts around the world, including interest rate swaps, and corporate and municipal bonds and loans. It was formally developed in the 1980s as a benchmark interest rate that could be utilized to facilitate syndicated loans and over time has been used in a wide range of financial products — most notably, derivatives contracts. The majority of contracts referencing LIBOR are for wholesale financial market products, and derivatives in particular.

LIBOR is perceived to represent the average interest rate at which banks can borrow from one another. It is currently calculated in five currencies and in seven “tenors”, or lengths of time (e.g., one-month, three-month or 12-month LIBOR). To calculate the rate, individual banks submit their estimates of the cost to borrow that day to the ICE Benchmark Administration, which in turn excludes the upper and lower quartiles, then averages the rest to get LIBOR. This is all regulated by the U.K.’s Financial Conduct Authority (FCA). Sixteen or fewer banks submit rates for LIBOR in each currency.

This sounds like a straightforward process, but in reality LIBOR has serious flaws. LIBOR submissions are informed by a small and dwindling number of actual transactions, making them less representative of what’s actually occurring in the market. While the precise volume of transactions underlying LIBOR is unknown, our best estimates show that, on a typical day, the volume of three-month wholesale funding transactions by major global banks was about $500 million. Compared to the $200 trillion of financial contracts referencing U.S. dollar (USD) LIBOR, that number is miniscule. This scarcity of transactions puts LIBOR at risk of conflicting with international best practices for benchmark rates. This declining volume of transactions — driven by long-term changes in bank funding patterns — means that most of the daily figures that banks give the ICE Benchmark Administration are simply judgment calls, and are not based on actual transactions. This reliance on expert judgment increases LIBOR’s vulnerability to manipulation.

These flaws have made public and private sector institutions increasingly concerned about LIBOR. Responding to these growing concerns, several institutions recently decided to stop providing LIBOR submissions to the ICE Benchmark Administration. As the number of LIBOR submitters declined, FCA Chief Executive Andrew Bailey announced that the FCA had forged agreements with banks to continue submitting rates through 2021, but that “the survival of LIBOR… could not and would not be guaranteed” after that.

2. What is the ARRC, what’s its role, and how is the Fed involved in it?

Because the existence of LIBOR can no longer be guaranteed, its publication could change or stop in just a few years. As a result, the financial system must prepare for a world without it. Considering the trillions of dollars of financial products referencing LIBOR, this is a tremendous and critical undertaking. That’s where the ARRC — the Alternative Reference Rates Committee — comes in.

The ARRC is a group that the Federal Reserve convened in 2014. It’s now comprised of over 25 private sector market participants — including representatives of banks, asset managers, insurers, and more — and over 10 official sector ex officio members.

The ARRC has had several responsibilities: to identify alternative reference rates to use in lieu of USD LIBOR; to develop a transition plan to foster use of these rates in financial products; to coordinate across cash and derivative products as market participants transition to the new rates; and to address risks in existing contracts that don’t adequately account for the possibility that LIBOR could become unusable.

Over the last two years, the New York Fed, in cooperation with the Office of Financial Research, developed several new reference rates based on overnight transactions in various segments of the Treasury repo market and began publishing them in April 2018. As the administrator of these rates, we designed them to be compliant with international best practices for financial benchmarks and accordingly have an internal oversight body to review our production process and ensure compliance with these standards. The ARRC selected one of those rates — the Secured Overnight Financing Rate (SOFR) — as its preferred alternative rate to USD LIBOR.

3. What is SOFR? And, is it really safer than LIBOR?

SOFR is a much more resilient rate than LIBOR for several reasons, all of which center on how it’s produced and the depth and liquidity of the markets that underlie it.

SOFR is a very broad measure of the cost of borrowing cash overnight collateralized by U.S. Treasury securities in the repurchase agreement (repo) market. As an overnight secured rate, SOFR better reflects the way financial institutions fund themselves today. And critically, the fact that it’s derived from the U.S. Treasury repo market means that, unlike LIBOR, it’s not at risk of disappearing in a few years.

Repo markets are diverse, and SOFR is based on transactions in three key market segments. The result is that the transaction volumes underlying SOFR (a daily volume of more than $700 billion in overnight repo transactions) are far larger than the transactions in any other U.S. money market, and they dwarf the limited volumes of daily transactions underlying LIBOR.

The fact that SOFR aligns with international standards, is based on actual transactions, and has a large volume of transactions underlying it — among other characteristics — makes SOFR a more robust and durable rate, and one that is less vulnerable to manipulation.

4. At what point could LIBOR disappear, and what happens then?

Banks haven’t agreed to provide LIBOR submissions after 2021, and the FCA has said they won’t attempt to compel submissions after that. If banks drop away from submitter panels after 2021, the ICE Benchmark Administration could stop publishing LIBOR, or the FCA could declare that the rate is no longer representative of the underlying market.

This pending deadline is highly concerning. After all, as of 2016, gross exposure to USD LIBOR was close to $200 trillion, roughly equivalent to 10 times the U.S. Gross Domestic Product. LIBOR is embedded into the fabric of the financial system, across a broad range of financial market participants and industries. This heavy reliance on it means there are considerable financial stability risks if everyone involved doesn’t work closely together to prepare for the possible end of LIBOR.

5. How’s the transition going?

Shifting to SOFR is a monumental task. Yet as former Bank President Dudley recently said, “we know the impact of a disorderly transition would be huge” so “moving this core piece of the global financial system to a firm and durable foundation is essential and worth the cost.”

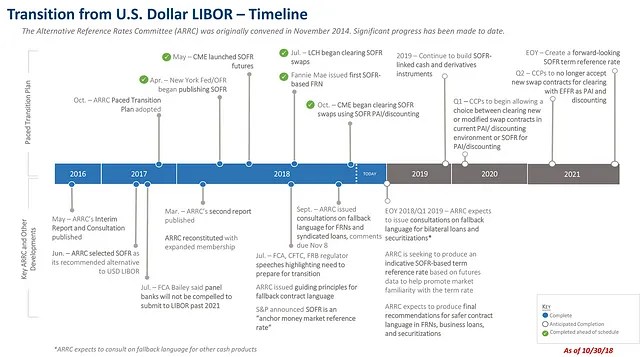

To support the transition to SOFR, the ARRC developed the Paced Transition Plan, which focuses on progressively building liquidity in derivatives referencing SOFR. In order to develop sufficient liquidity, the ARRC is focused on supporting the launch of SOFR-based financial products in the market and creating a forward-looking term reference rate based on SOFR by the end of 2021.

This effort is ahead of schedule. Since we started publishing SOFR in April, CME launched SOFR futures, LCH and CME began clearing interest rate swaps referencing SOFR, and numerous institutions have issued SOFR-linked floating rate debt — among other accomplishments. That’s progress!

As the ARRC progresses with the Paced Transition Plan, financial institutions need to be aware of developments and seriously consider the impact of LIBOR’s cessation in a manner consistent with their exposures and risks.

In addition to the Paced Transition Plan, the ARRC is also working to address the fact that most contracts for cash products do not adequately account for the possibility that LIBOR will cease to be produced. This summer, the ARRC released guidelines for “fallback” language to include in new financial contracts that reference LIBOR, to ensure the contracts continue to be effective in the event that LIBOR is no longer usable. The ARRC recently issued public consultations on fallback contract language for floating rate notes and syndicated business loans, with the goal of recommending final language in the coming months that market participants can adopt voluntarily. By the end of this year, the ARRC expects to issue consultations on fallback language for bilateral loans and securitizations.

We all have a lot of work ahead to ensure a successful transition to SOFR. There’s no doubt that this transition is essential to a more sound and resilient financial regime. There are still considerable obstacles to overcome in the next three years, but in the interim, we’ll continue producing robust and durable reference rates and coordinating through the ARRC on this critical effort.

Fast Facts:

Why is SOFR a strong alternative to LIBOR?

*Based on a large volume of actual transactions

*Less vulnerable to manipulation

*Clearly aligned with international standards

*No cessation risk

Transaction volumes underlying LIBOR vs. SOFR:

*SOFR: average daily volume of more than $700 billion in overnight repo transactions

*LIBOR: unknown; while it’s not an apples-to-apples comparison given the terms of overnight funding and three-month funding transactions, our best estimate is that an average daily volume of about $500 million of three-month funding transactions underlie LIBOR

Where to get updates:

*Sign up for ARRC alerts here.

*Sign up for SOFR data alerts here.

This article was originally published by the New York Fed on Medium.

The views expressed in this article are those of the contributing authors and do not necessarily reflect the position of the New York Fed or the Federal Reserve System.