This is part of an ongoing educational series on nonbank financial institutions.

Nonbank financial institutions (NBFIs) play a critical role in private credit, which has recently become a key source of financing for corporations. In this article, we describe private credit and its recent growth, the role of NBFIs in the private credit ecosystem, and how private credit interacts with the Federal Reserve’s monetary policy, prudential supervision, and financial stability objectives.

What Is Private Credit?

Although there is no universal definition, private credit generally refers to a loan that is negotiated directly between a borrower and a small group of nonbank lenders. These NBFI lenders are typically alternative asset managers, such as private equity firms, who package the loans in different investment vehicles. Other NBFIs—like pension funds, insurance companies, and sovereign wealth funds—then invest in those vehicles. Unlike other sources of corporate financing, most private credit loans do not trade in a secondary market. They also tend to have higher interest rates and below-investment-grade credit ratings compared to other types of debt. Private credit loans also typically have stronger investor protections than publicly traded corporate debt, and they rank above other debt obligations in a company’s capital structure, meaning they need to be repaid first. For borrowers and their owners, many of which are private equity sponsors, the loans can be tailored to each borrower’s needs, a feature they find attractive.

In the decade after the global financial crisis, small- and medium-sized companies were the predominant borrowers of private credit loans, using them to finance leveraged buyouts and acquisitions. At the time, many of those companies were considered too small or too risky to obtain financing from banks or public credit markets. Recently, however, larger companies and those with higher credit ratings—that historically borrowed in the high-yield bond or leveraged loan markets—have also borrowed in the private credit market.

The Size and Growth of the Private Credit Market

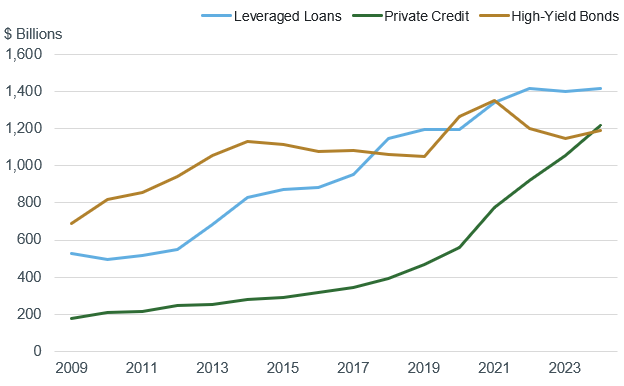

The size of the U.S. private credit market is approaching $1.3 trillion, as seen by the green line in the chart below. This accounts for around 30 percent of debt issued by below-investment-grade-rated companies, up from 13 percent immediately following the global financial crisis.

Estimated Market Size of Below-Investment-Grade U.S. Corporate Credit

Source: Preqin, BDC Collateral, Pitchbook, ICE BofA Indices, as of December 2024

Investors add U.S. private credit exposure to their portfolios through two main investment vehicles managed by NBFIs:

- Private credit investment funds, representing $800 billion of the private credit market, draw capital predominately from institutional investors, including NBFIs like pension funds, insurance companies, and sovereign wealth funds. These funds are often structured as limited partnerships where the general partner is the fund’s manager and the limited partners are the end-investors. During the fundraising period, limited partners commit capital which is invested later as opportunities arise. Investor capital is typically locked up until loans are repaid, often for five to seven years.

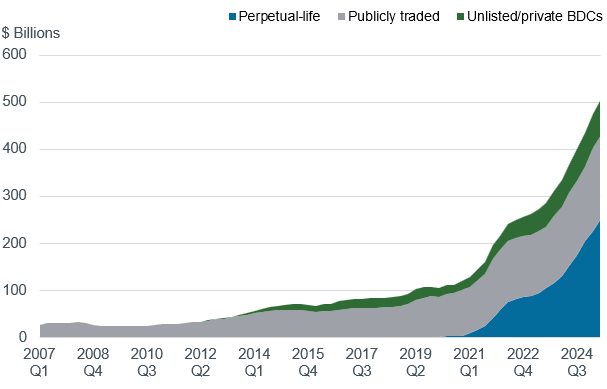

- Business development companies (BDCs), making up $500 billion of the private credit market, make direct loans to small- and medium-sized businesses. BDCs must distribute at least 90 percent of their income to their shareholders, most of whom are retail and high-net-worth individual investors. BDCs have grown rapidly in recent years, as seen in the chart below. This is in large part due to perpetual BDCs, which raise capital continuously and do not have a planned initial offering or liquidation.

Business Development Company Total Assets by Type

Private credit’s growth is the result of its market’s structure, policy developments, and market volatility. From a market structure perspective, borrowers prefer private credit over syndicated bank loans and publicly traded bonds due to certainty of loan execution, fewer disclosure requirements, and far fewer lenders. Investors are attracted to higher expected returns and lower volatility compared to public bonds, thanks in part to private credit loans not trading in secondary markets. For example, during the COVID-19 pandemic, companies and their owners appreciated the flexibility and ease of communication that private credit lenders offered to manage the temporary shock. In addition, investor demand for private credit funds was strong amid the demand for higher investment returns.

To adhere to new policy regulations implemented in response to the global financial crisis, some large and regional banks retreated from providing credit to middle-market companies to meet higher capital requirements and improve their risk-based capital ratios. As a result, many such companies turned to private credit lenders to meet their financing needs.

Also, during the March 2023 episode of banking stress and public credit market volatility, increasingly more large companies and their private equity sponsors preferred to borrow from private credit lenders given the certainty of loan execution.

Why Is Private Credit Important to the Federal Reserve?

The growth of private credit comes with significant implications for the Fed’s core responsibilities of monetary policy, prudential supervision, and financial stability.

Monetary Policy: Once the Federal Open Market Committee (FOMC) sets the stance of monetary policy throughits policy rate to stimulate or restrain economic activity, the Fed implements that policy through transactions with counterparties, including banks and NBFIs. They, in turn, transmit the policy through their lending, investment, and asset allocation decisions, influencing financial markets and the real economy. With private credit, this transmission is primarily done through two channels.

- Interest rate channel: Changes in the policy rate can influence borrowing costs in different ways, depending on the type of debt instrument. For companies with fixed-rate corporate bonds, changes in short-term interest rates affect borrowing costs when a company issues new debt or refinances its maturing debt, which occurs periodically over several years. For companies with floating-rate loans, changes in interest rates affect borrowing costs more quickly because the loans’ interest rates are adjusted frequently, typically quarterly based on a short-term reference rate.

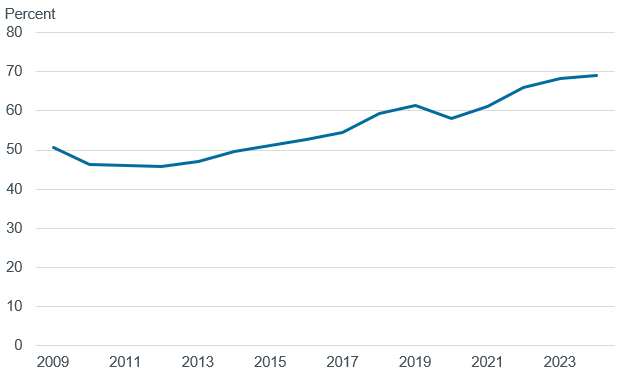

The growth in private credit has shifted companies’ debt profiles toward floating-rate loans, so the passthrough of changes in the policy rate occurs more quickly. As shown in the chart below, the share of floating-rate debt for below-investment-grade firms has risen materially over the past decade, reflecting the growth in both private credit and leveraged loans.

Estimated Share of Floating Rate Debt for Below-Investment-Grade Firms

Source: ICE BofA Indices, Preqin, Pitchbook, BDC Collateral, as of December 2024

- Credit channel: Changes in the FOMC’s monetary policy stance can affect banks’ and nonbank lenders’ decisions to extend credit directly to companies or to underwrite new loans. Before private credit, this meant that banks’ sensitivity to short-term rates strongly affected the corporate sector’s ability to secure financing. During the 2022-2023 rate tightening cycle, banks exhibited some caution in extending credit to businesses, while nonbank private credit lenders deployed a significant amount of capital to borrowers. This potentially decreased the expected contraction in credit availability.

Prudential Supervision: The largest banks supervised by the Fed have meaningful interconnections with private credit lenders. Compared to before the global financial crisis, banks today hold fewer middle-market loans and more NBFI loans, including private credit funds and BDCs. For example, recent Federal Reserve Board research found that the largest U.S. banks have extended around $95 billion in loans to private credit lenders. This figure may underestimate the overall exposure because it does not include all banks. Activities and related risks of banks and private credit funds are intimately interwoven, such that under an extreme economic scenario, stress in the private credit industry could affect the banking system. Monitoring these exposures and better understanding their potential risks is critical for effective banking supervision. In addition, private credit’s continued growth and NBFIs’ expansion into areas traditionally dominated by banks could impact bank revenues and profitability, which are also important for assessing the safety and soundness of financial institutions.

Financial Stability: As important funding sources for businesses, private credit lenders could affect financial stability.

Some market participants believe the financial system is safer with private credit lenders, holding corporate loans instead of banks. These nonbank lenders typically have limited asset-liability mismatches and modest leverage levels. Additionally, the willingness of nonbank lenders to extend credit in periods of volatility and the flexibility on loan terms they offer—such as adjusting interest repayments or extending a loan’s maturity—could help mitigate corporate defaults.

On the other hand, the rapid increase in capital raised by private credit lenders and the competition to deploy it could loosen loan underwriting standards and result in a misallocation of credit. That, in turn, could lead to more defaults and, in an extreme scenario, transmit risk to the banks that financed private credit vehicles. Additionally, the links between private credit and the broader set of NBFIs are growing and becoming more complex through various structured products, which can make it difficult to detect risks and understand the different layers of leverage in the financial system. Finally, nonbank private credit lenders do not have access to central bank liquidity facilities in the event of a severe economic downturn.

The Federal Reserve and other member agencies work through the Financial Stability Oversight Council to evaluate these and other financial stability risks that may be posed by private credit lenders.

In Summary

Having grown from $500 billion in 2020 to almost $1.3 trillion today, private credit is an increasingly important source of financing for companies. Private credit’s growth significantly affects how the Fed’s objectives of monetary policy, prudential supervision, and financial stability are achieved. To stay informed on this and other important trends related to NBFIs, the New York Fed frequently updates a curated selection of research, analysis, and external resources on its website.

Daniel Maddy-Weitzman is a policy and market analysis principal in the New York Fed’s Markets Group.

Also in this series:

The views expressed in this article are those of the contributing authors and do not necessarily reflect the position of the New York Fed or the Federal Reserve System.