The Federal Reserve System is the central bank of the United States. Its key entities are the Board of Governors, which is an independent federal government agency, 12 regional Federal Reserve Banks, and the Federal Open Market Committee (FOMC). The FOMC includes members of the Board of Governors, the president of the Federal Reserve Bank of New York, and four other regional Reserve Bank presidents who serve on a rotating basis. You might hear these entities more often referred to collectively as “the Fed,” for short.

The Fed was established in 1913 to stabilize and unify the nation’s financial system. Before the Fed’s creation, the U.S. financial system repeatedly failed to supply appropriate money and credit to meet the economy’s needs—sparking a series of financial crises and boom and bust cycles in the economy.

The Fed is responsible for conducting monetary policy, promoting the stability of the financial system, promoting the safety and soundness of the banking system by regulating and supervising its activity, fostering payment and settlement system safety and efficiency, acting as the fiscal agent for the U.S. federal government, and promoting consumer protection and community development.

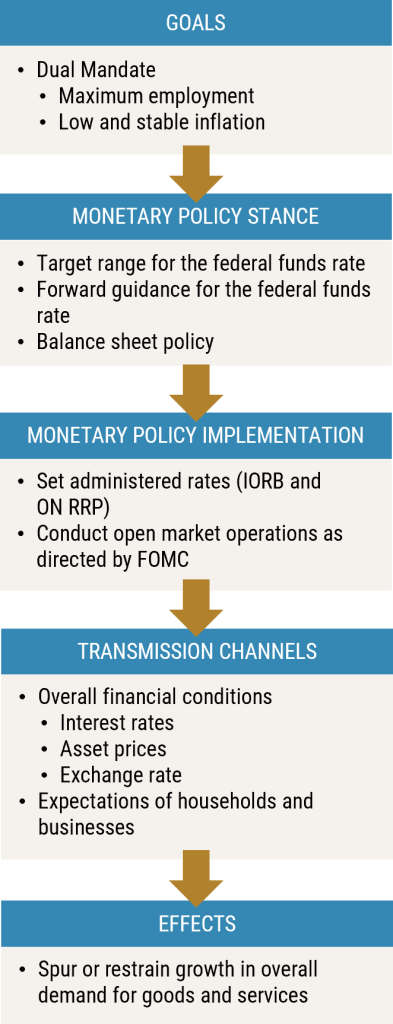

By law, the FOMC sets monetary policy to promote maximum employment and stable prices. These goals are more commonly known as the “dual mandate”. In this article, we discuss how the Fed sets and implements monetary policy to achieve its dual mandate.

Setting the Stance of Monetary Policy

The FOMC is responsible for setting the stance of monetary policy to achieve its dual mandate. The “stance” of monetary policy refers to whether policy is stimulating or constraining the labor market and inflation. The policy stance is primarily set by establishing a target range for the federal funds rate, which is the interest rate at which banks can borrow reserves in private markets on an unsecured, overnight basis. Reserves are deposits that banks hold at the Fed and are used for activities like managing liquidity, making payments, and meeting requirements set by bank regulators. To summarize conditions in the federal funds market, the FOMC focuses on the effective federal funds rate (EFFR), an index calculated daily by the New York Fed based on individual federal funds transactions in the market.

Adjustments to the target range for the federal funds rate are passed through to a broader set of interest rates and overall financial conditions. Changes in interest rates and financial conditions influence decisions made by households and businesses, and therefore the broader economy, through several channels, including the cost of credit. In general, higher interest rates tend to reduce economic activity and inflation by discouraging borrowing and spending, while lower rates tend to stimulate activity and prevent inflation from being too low by providing more incentive for borrowing and spending.

While adjusting the federal funds target range is the primary means by which the FOMC changes the stance of monetary policy, it can also do so by communicating how that stance might change in response to evolving economic conditions. The nature of that anticipated response is commonly known as the FOMC’s “reaction function.” This communication has occasionally taken the form of “forward guidance,” which establishes explicit outcomes or time frames for future policy actions. Additionally, the FOMC can adjust the stance of monetary policy by changing the size and composition of the Fed’s balance sheet, which we’ll discuss later in this series.

Keeping the Federal Funds Rate within the Target Range

Once the FOMC decides on the appropriate stance of monetary policy, the Fed uses various tools to implement that monetary policy stance. A key aspect of successfully implementing monetary policy is having strong control of short-term interest rates, meaning that the federal funds rate remains well within the FOMC’s target range. Since the Global Financial Crisis, interest rate control has been achieved through a “floor system” that relies on maintaining, at a minimum, an ample level of reserves, supplied through the Fed’s balance sheet.

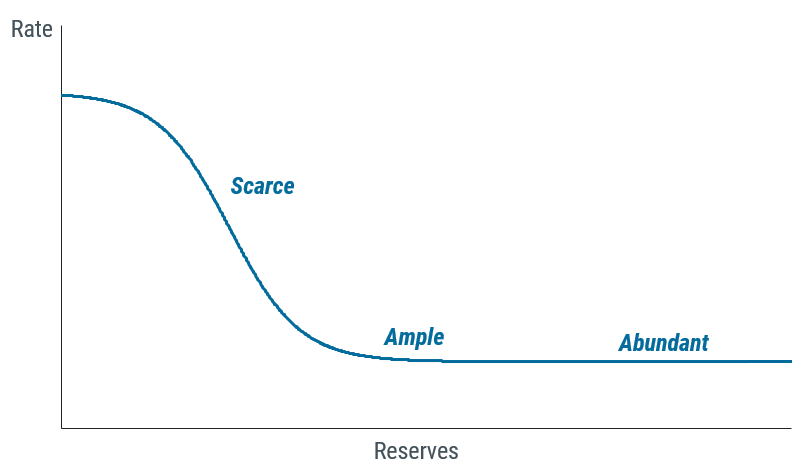

This is visualized in the below chart, which shows an illustrative demand curve for reserves from banks. Ample reserve supply creates an environment in which the interest rate (that is, the cost of borrowing reserves) in the federal funds market, shown on the vertical axis, is not particularly sensitive to significant short-term variations in the supply and demand of reserves. This can be seen in the gently sloped portion of the curve. This contrasts to environments of scarce reserves, in which the interest rate is highly reactive to supply and demand variations (the steep part of the curve), and abundant reserves, in which the interest rate is insensitive to such variations (the flat part of the curve).

Stylized Reserve Demand Curve

In a floor system, the federal funds rate is primarily controlled by administered rates that are set by policymakers. The two key administered rates are the interest rate on reserve balances (IORB), which is the rate of interest banks earn on their balances left at the Fed, and the interest rate on the overnight reverse repo (ON RRP) facility, which provides an overnight collateralized investment opportunity to a broader range of money market participants.

How the Administered Rates Work

Together, the IORB and ON RRP rates set the “floor” for short-term interest rates. That directly affects the interest rate levels corresponding with the gently sloped and flat portion of the demand curve above. The IORB establishes a floor for rates below which banks are highly unlikely to lend out their reserves; the ON RRP rate helps reinforce the floor.

Only banks are eligible to earn IORB. Some other financial institutions, such as Government Sponsored Enterprises, including the Federal Home Loan Banks (FHLBs), have deposits at the Fed but are not eligible to be paid interest on those holdings. Those firms may therefore be willing to lend funds at rates lower than the IORB. The ON RRP facility provides a similar disincentive against lending below the ON RRP rate to a wider set of nonbank investors, including FHLBs. In this sense, the ON RRP rate reinforces the floor set by IORB.

Usage of the ON RRP facility can vary significantly based on money market conditions. Even when it is not used, the facility still supports interest rate control, since the simple fact that it is available helps institutions eligible to participate in the facility to negotiate rates on private investments that are above the ON RRP rate. When more attractive rates are not available, the facility is then an alternative investment option.

In a floor system, the supply of reserves is high enough that it is not necessary to actively manage reserves. Still, the Fed may need to adjust reserve supply over time to accommodate longer-term growth in demand for reserves and other Fed liabilities. To do that, the New York Fed’s Open Market Trading Desk conducts open market operations, which affect the size of the Federal Reserve’s balance sheet—the subject of our next article.

Eric LeSueur is an advisor in the New York Fed’s Markets Group.

Linsey Molloy is an associate director in the New York Fed’s Markets Group.

Will Riordan is an advisor in the New York Fed’s Markets Group.

Josh Younger is an advisor in the New York Fed’s Markets Group.

Also in this series:

The views expressed in this article are those of the contributing authors and do not necessarily reflect the position of the New York Fed or the Federal Reserve System.